What We Assume about the Assumption of Mary, Mother of Jesus

For skeptics and believers

A guest post from my friend Kelley Mathews:

Just about the time we kids were trying not to think about school starting, a holy day of obligation would roll around to remind us our time was short. Every August 15, we trotted off to church for an extra Mass dedicated to remembering how, after Jesus’s mother died, her body was snatched up to heaven. Or, was it that she didn’t really die but got to join Jesus in heaven body and soul when it was “her time”? Most of all I wondered why I should care.

The Assumption of Mary seemed … unusual. I had questions.

Turns out, I’m in good company.

Terms and Conditions

Let’s define a few terms and set the stage. The deathbed scene of Mary, the mother of Jesus, goes by two related terms. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, it is called the Dormition. Derived from the Latin “dormire,” meaning sleep, the word refers to the “Sleep of Mary,” sleep being a common euphemism for death. The term implies that she experienced a typical human death before anything supernatural happened to her body.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the celebration of Mary’s final moments is called the Assumption, referring to the belief that her body was taken up—assumed—into glory without experiencing decay. The pope who declared the Assumption as official church teaching (dogma) was purposely vague in describing the timing, leaving it open to individuals to believe she was “assumed” before or after she died.

The average Protestant generally either denies the Assumption happened at all or doesn’t know anything about it because Mary as a subject of study is considered a low priority. There is a real fear that paying attention to her is too “Catholic.” I hope to allay such skepticism with insight into Mary’s value to all Christians.

Scriptural Foundations

The biblical text mentions Mary by name a handful of times, but those mentions paint a picture of her familiarity and acceptance among her son’s devoted followers. After we meet her chatting with Gabriel in Luke 1, she displays her theological chops with her Magnificat (also in Luke 1), her grit on her way to Bethlehem at nine months along, and her maternal instincts when pre-teen Jesus disappeared. During his adult ministry, she pops into the Gospels periodically. Those mentions show that she was often present with Jesus during his ministry and, critically, accompanied him to the cross. Jesus’s words to her and John hint at her future:

When Jesus saw his mother there, and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to her, “Woman, here is your son,”and to the disciple, “Here is your mother.” From that time on, this disciple took her into his home (John 19:26–27).

Mary at Pentecost, surrounded by the disciples, with the Spirit’s tongues of fire descending on them. By Titian, 1553. Venice. https://www.visualmuseum.gallery/gallery/the-descent-of-the-holy-ghost

Mary also joined the 120 disciples on the day of Pentecost (Acts 1–2), meaning she was present not only at the birth of the Savior but at the birth of his church as well. Post-biblical tradition places her with John in the city of Ephesus, where she remained a source of encouragement and strength for the growing church.

Mary’s deathbed scene is not in Scripture. Some traditions say she was in Ephesus when she reportedly died and the assumption of her body occurred. Other traditions put her in Jerusalem.

A quick primer on church history: Prior to 1054, the church was largely unified, and scholars’ teachings spread widely. In the chart below, follow the gray line until it splits into red and blue. The Great Schism created two major wings of Christendom: Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic. In the 1500s (along the red line), the reformers broke away and (green line) began what came to be known as Protestantism.

My Protestant readers … church history did not begin with Luther. So when we talk about the Church Fathers and medieval religious activities and teachings, they all belong to you, too. It’s legitimate to have questions, and even reject some teachings which obviously contradicted Scripture then (just as we do now), but for better or worse that history belongs to all Christians.

When did the tradition surrounding Mary begin?

One of the earliest texts detailing the Dormition comes from the seventh-century Byzantine scholar Maximus the Confessor. In his book The Life of the Virgin, he claims that God revealed “her glorious Dormition to her in advance” just as he had sent Gabriel to announce the Incarnation to her earlier. She then informed and consoled those around her, submitted to her Son’s divine will, and awaited her moment. The apostles came to visit, including Paul, and with much prayer and worship, they all glorified God. Then Christ himself, with a host of angels, descended to take her home with him before her body experienced death.

In Maximus’s telling, Mary did not die. Her bodily perfection at death was, in his mind, a continuation of her physical and moral perfection throughout her life. It was not a stretch for him to believe Christ would “alter the course of nature” at her death since he had done so at the Incarnation.

Perfect Mary?

What do I mean by “moral perfection”? Catholic and Orthodox teachings consider Mary to have been born without original sin, a stance based on Gabriel’s declaration to her that she was “highly favored” (Luke 1:28). If the Lord had always planned to choose Mary to bear his son, the logic goes, she would have been born in an unusual state of grace. And if she was sinless, she would also have remained a virgin, untouched by a man—another form of purity.¹ And if all that were true of Mary, then her body would not have been allowed to experience decay.²

When he declared the Assumption to be Catholic dogma in 1950, Pope Pius XII quoted St. Germanus of Constantinople, who “considered that the preservation from decay of the body of the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary, and its elevation to heaven as being not only appropriate to her Motherhood but also to the peculiar sanctity of its virgin state … it follows that it is not in its nature to decay into dust, but that it is transformed, being human, into a glorious and incorruptible life, the same body, living and glorious, unharmed, sharing in perfect life.”

Mary was definitely something special to the early and medieval church.

Imperfect Mary

Protestants push back on the exaltation of Mary, pointing to scriptural passages that affirm the sinfulness of all humanity:

Romans 3:23 “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.”

Romans 5:12 “just as sin entered the world through one man and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned…”

Additionally, Mary herself looks to God as her savior (Luke 1:46), a comment that seems to confirm her sense of her own depravity. She was human like the rest of us.

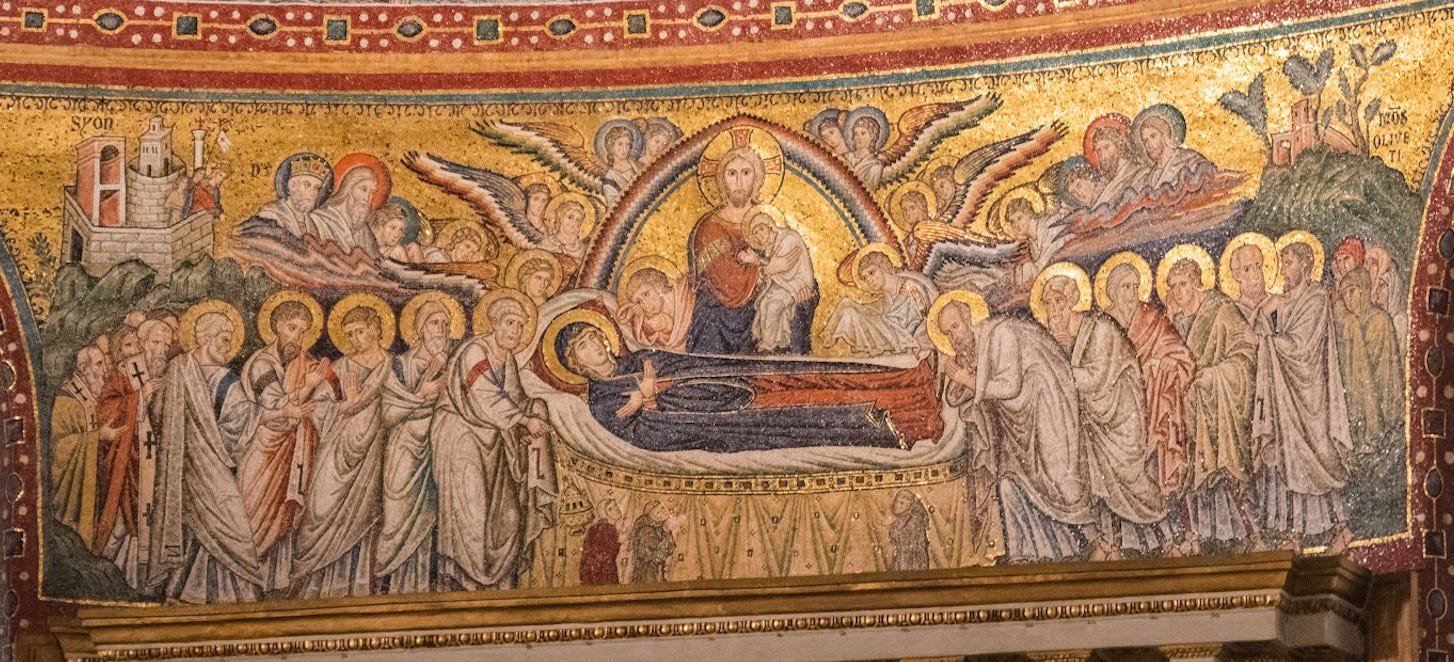

The Coronation of Mary: a mosaic in the apse of Basilica Papale di Santa Maria Maggiore, in Rome, Italy. https://www.visualmuseum.gallery/gallery/coronation-of-the-virgin-closeup/

In the centuries since the first generation of Christians lived, both Scripture and historical records have painted a complex picture of the mother of Jesus. Fantastical things were said about her that elevated her in the eyes of millions as a person set apart from the rest of us. In fact, I will be tracing the history of Mary’s exaltation through the centuries as part of my doctoral dissertation. She is known as the “queen of heaven” in some circles, a far cry from the peasant girl of Luke 1.

As postmoderns today, we would rather have just the facts, thank you. Protestants in particular put ultimate weight on Scripture over tradition, not only because Scripture is God’s Word but also because the doctrine of depravity reminds us that humans—including church leaders—are finite and imperfect. We will get things wrong, such as the way we interpret Scripture.

Original Sources

Theologians in all three church traditions value the teachings of the early church. Many of our core doctrines were hammered out in the second–fifth centuries. Maximus, a seventh-century scholar, based much of his book on older sources such as Athanasius and Gregory of Nyssa, whose teachings he considered to be true.

But Stephen Shoemaker, the editor of the recent English Life of the Virgintranslation, notes in his introduction that, despite Maximus’s confidence, “there is no reason to assume that these supplements to Mary’s biography bear any relation to the historical realities of earliest Christianity.”

In other words, Maximus took a skeleton of stories from the third and fourth centuries and fleshed them out in his elaborate Life of the Virgin. We can compare his claims to Scripture and perhaps rule out some of them, but we can’t know exactly what happened on Mary’s deathbed.

So what is the value of his work?

Does the Assumption Matter?

Shoemaker again: “The traditions gathered together in this earliest Life of the Virgin are invaluable for the insight they offer into how Christians at the end of antiquity had come to remember the mother of their Lord and how they interpreted her significance in the life of her son and the beginnings of the Christian faith.”

In the many teachings about Mary we learn not so much what happened to her but what people thought about her. We understand what qualities they valued in their spiritual heroes.

For those who accept the historicity of the Assumption, it is important to remember that just because something is written by a Church Father doesn’t mean it is true. They held all sorts of views that have been proven wrong and/or contrary to Scripture. We are all products of our times, and they were fallible men influenced by their worlds.

And for those inclined to deny the Assumption, how do you know? Just because it’s not in the Bible doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Some assumptions (no pun intended, but it is a little delicious) must be addressed directly:

Regarding Mary’s moral purity: Is it possible that Mary was morally perfect? Scripture denies that.

Regarding the Dormition: Is it possible that Christ raised his mother’s body at death (either just before or just after)? Scripture doesn’t tell us. But we do see two other examples of humans not dying physically (Enoch in Genesis 5:24; Elijah in 2 Kings 2:11). And God can do whatever he wishes. So the Assumption/Dormition, while impossible to prove, is not incompatible with Scripture.

One biblical concept the Dormition affirms is the dignity of the physical body. Gnosticism, a belief that spirit was superior to material, led to a variety of erroneous and damaging teachings regarding the human body. But the church emerged from that philosophical debate mostly intact (though gnostic teaching rears up every generation in some form). The widespread belief in Mary’s Dormition honored the human body and, even more intriguingly, the female body. The belief in the supernatural assumption of her body revealed a deep hope in the bodily resurrection of all believers.

Scripture is God’s authoritative word. All teachings regarding non-biblical events or ideas must be reconciled to Scripture’s teaching. However, it does not speak about all things. God reveals himself in the Bible, not necessarily information about all that we wish to know.

A Judgment Call

So did the Assumption of Mary happen? Christians disagree. When faced with contradictory conclusions to theological questions, we may never agree to agree. But we can ask if and how these controversial teachings point us to Jesus. Does the Dormition of Mary glorify Jesus? The traditional explanation is rooted in, among other things, the understanding that Jesus and Mary enjoyed a very close relationship, with Mary constantly pointing people to her son. Everything she did was to glorify him. So by assuming her body incorrupted, as generations of Christians believe(d), he was honoring her devotion to him—and anticipating the physical nature of the coming kingdom.

If Mary experienced a typical human death and was buried with honor by those who loved her, Jesus is glorified in that, too. Her utter devotion to him ensured that she immediately joined him in spirit (“… to be away from the body and at home with the Lord,” 2 Corinthians 5:8). She is one of us, though arguably the most loyal of all his followers, joining with us to proclaim his greatness.

Either way, if Mary has a crown, she’s throwing it at his feet, too.

Kelley Mathews is a theologically trained writer and editor and an unabashed fiction lover. She holds a ThM from Dallas Theological Seminary and is pursuing a doctorate a Houston Christian University. Kelley has experience in publishing, social media and content marketing, website management, book reviewing, book authoring, contributing, editing, and proofreading over the last 25+ years.

Cover image: The Dormition of Mary, a mosaic in Basilica de Maria Maggiore in Rome. Photo by Shala Graham, used with permission.