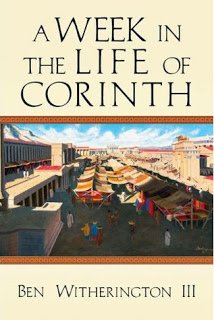

A Week in the Life of Corinth

Rewind back to the time of Paul when he lived in Corinth andmade tents alongside Priscilla and Aquila. In that day, a master expectedaccess to his slaves’ bodies in every way, adoption was mostly aboutinheritance, and the oral slant of the culture meant rhetoric ruled.

Into this world New Testament scholar and multi-published author Ben Witherington III introducesthe character Nicanor and his patron Erastos in A Week in the Life of Corinth (IVP Academic). Weaving a plot abouttheir lives, the scholar provides a glimpse into the world of the earliestChristians.

The fact that an academic publisher has produced the bookmakes obvious that which becomes even clearer from the back cover copy: thatthe plot serves the content rather than vice versa. Flipping through the pages, readers find black-and-white photos as well as non-fiction text boxes providing information that further exegetes the culture,explaining background information that corresponds to theplot. Clearly, Witherington has set out to educate, and he has done so in the formof a story. Here content trumps plot, characterization, and setting.

Many in the fiction-writing world consider this sort of“edutainment” a no-no, arguing that the information must serve the story andnot vice versa. But Pilgrim’s Progress hasn’tdone too badly, and John Bunyan did the same thing—okay, less overtly. But heck, DanBrown did it too, though also less overtly, with TheDaVinci Code.

Brown, however, is a far better fiction writer. In this work, theplot is predictable and characters suffer from underdevelopment. They talk instiff dialogue, often telling each other what they would already know so thereader can learn. Their content-filled speech along with overlong dialogue tagscould benefit from the effective use of beats.

As for style, the author selects a rather uninteresting rangeof verbs and nouns, using “was” and “were” and “is” far too often, along withoverusing "had" and "has." Long sentences at times serve as entireparagraphs—acceptable in Paul’s day when writing material was expensive andscarce, but not in 2013.

The total effect is the mirror of what happens when fictionwriters don’t know about biblical backgrounds, so they write the Esther storyas a romance. Here a biblical scholar has not mastered the art of writtenstorytelling. And we need both excellent storytelling and good background expertise.(Ben-Hur is an example of a work thatweds the two fields in a way that gives readers a story for the ages.)

Nevertheless, I recommend this book. Highly. It won’t getnominated for the National Book Award. But it does capture the imagination much morethan would a textbook on first-century backgrounds. Witherington has given readers a primeron first-century backgrounds that delivers some of his vast knowledge in anaccessible form. Those who read his book will better understand the New Testament and thus make better correlations between the biblical text and our lives. How many novels can make that claim?

|

| Paul would have been familiar with the "bema" or judgment seat in Corinth. |