Reading that Transforms

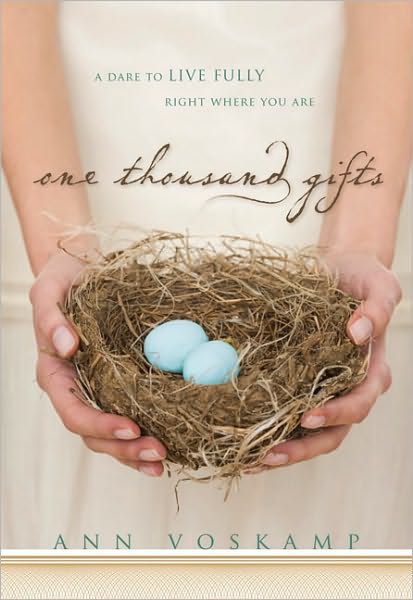

Every Sunday afternoon I try to disengage from work and electronictechnology to engage in nap-taking, kitchen-puttering, and/or spiritualreading. By spiritual reading I mean reading that helps me think more deeplyand theologically about a topic. For the past few months I’ve been meanderingmy way through two books during this time—John Dyer’s From the Garden to the City and Ann Voskamp’s One Thousand Gifts.

Voskamp’s book focuses on making gratitude a way of life.The author often has astounding insights, but to be honest I have to limitmyself to one chapter per week because she has a nasty habit of writing purpleprose (i.e., writing passages with such flowery language that the words drawattention to themselves, thereby distracting the reader from thinking of theconcepts they illustrate). But it’s worth the work to discover how she sees gloryin the ordinary. In the past forty-eight hours, for example, I have relishedthe taste of hot, homemade crock pot applesauce; marveled at the beauty of mydaughter’s smile; appreciated the design in a pair of Tom’s shoes; noticedwhimsy in cloud formations; and marveled at the fur of my cat. Voskamp takesthe reader one step beyond such discoveries, though, to the point of gratitudefor them. It’s tough to stay angry about something when we’re giving thanks.

Dyer’s book, which I finished this past Sunday, is of a different sortfrom Voskamp’s. It’s subtitled, “The Redeeming and Corrupting Power ofTechnology,” and it provides insight regarding how to think rightly about technology.

In this week's chapter (my favorite) Dyer likened our constantchecking of webtracking stats to King David’s numbering his troops (2 Sam. 24;1 Chron. 21). “What was once available only to kings,” Dyer argues, “is nowavailable to all of us. At any moment we can get up-to-date statistics on ourfans, friends, and followers. Again, the statistics themselves are not sinful.The problem is that the more we use it, the more tempted we are to value whatthe technology values—numbers—over what the Scriptures would have usvalue.” (Or, I imagine, the flip side of devaluing ourselves when these numbers stink.)

Dyer also made application from how the elder John viewedthe technology of his day—letter writing. In 2 John 12 we read, “Though I havemuch to write to you, I would rather not use paper and ink. Instead I hope tocome to you and talk face to face, so that our joy may be made complete.” A letter, Dyer notes, typically goes from oneisolated individual to another. And the elder John’s joy was never “complete” with such isolation. Joy came only when he had face-time with the community. Clearly he viewed technology-mediatedrelationships as inferior to embodied relationships.

I immediately thought of a parallel. I love keeping upwith my niece Heather through Words with Friends, Facebook, and blog comments,but none of that came close to the joy I experienced last month sitting in herkitchen in Portland and later sharing a meal with her and her husband. And it bugs me when I call on someone in their living room and they constantly check out of the conversation to check email on the smartphone. Or students check email during class discussion time.

Bothbodied and disembodied forms of communication are real, Dyer argues, but onlythe face-to-face contact offers real joy. The danger for us, then, is to allowvirtual communication to replace “the kind of life-giving, table-oriented lifethat Jesus cultivated among his disciples.” We should use technology, then, inservice to the embodied life and not the embodied life in service totechnology.

Interestingly the two books have one application or "take away" in common for me: to live fully right where I am. To embrace face time with people instead of checking emails when they're present. And to notice the beauty and give thanks for it in the "today" rather than always looking toward tomorrow.